Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part 1)

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part 2)

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part 3)

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part 4)

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part 5)

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect

(Part One)

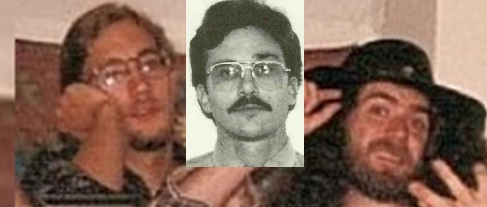

Unidentied man (left) in a photo with Gardner Museum security guard and heist suspect Rick Abath (right)

Rod Ramsay mug shot from June 7, 1990 (center)

Though his name has never been raised with the public as a Gardner heist suspect by either investigators or the news media, Roderick James Ramsay, a former Boston resident, arrested on espionage charges in Tampa, FL, on June 7, 1990, just ten weeks after the robbery, is certainly someone who remains worthy of consideration. Ramsay was convicted of espionage two years after his 1990 arrest and spent over a decade in prison after his conviction in 1992.

The Boston Globe, New York Times and other news media long ago abandoned hard reporting on the Gardner heist case in favor of “conjecture based on a

theory,” mutely disseminated by government officials

and their surrogates, like former FBI Gardner heist lead investigator Geoff Kelly, who in retirement has updated his narrative

(changed his story). He now claims that the security guard Rick Abath was indeed in on the robbery, after publicly suggesting otherwise

on numerous occasions for over twenty years. Kelly, who has a book on the Gardner heist investigation coming out in 2026, bases his conclusion on information known to investigators the first week; that the Museum security system did not record anyone going into the Blue Room gallery,

where Manet’s Chez Tortoni was taken, with the exception Abath, who was recorded entering the gallery twice.

As Kelly himself said on CBS Good Morning ten years earlier, in 2015: "Someone went into the

Blue Room that night, and the only one that went in that room that night was the security guard [Rick Abath], according to the motion sensor printouts."

But when Abath refused to speak with CBS Good Morning, and said publicly he was not doing anymore interviews, the FBI and its surrogates reverted to their false narrative that Abath was tricked into letting the thieves in.

By April of the following year, in 2016, the Gardner Museum’s secuirty director Anthony Amore, who is also

the FBI’s chief public relations surrogate on the case said:

“We have nothing to point at to say that he [Abath] was involved.”

An FBI podcast on the case starring Geoff Kelly in June of 2023 begins:

“In March 1990, art thieves conned

their way into the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.” Less than two years later, however,

Kelly told the Boston Globe he was convinced Abath was indeed involved.

But since Abath, who by his own admission was the person solely responsible for letting the thieves into the Museum, if he was indeed involved, which has always seemed

very likely, then the thieves did not con their way into the museum.

The stalement ended a year after Rick Abath died, when Abath could no longer defend himself, but more importantly when Abath could no longer put the FBI's investigative team and its

coterie of surrogates into a position of having to defend themselves. Kelly, in retirement and in need of some juice for his book, now says he believes Abath was involved,

which everyone, not in one way or another riding the FBI's disinformation gravy train, or too timid to speak out, had been saying for over a dozen years, when Abath himself started

going public about his role as the guard who let the thieves in,

after being shielded from public scrutiny for over 20 years.

Meanwhile, real facts, which would lead to the kind of real answers the public is surely entitled to after close to four decades, remain unreported.

Among those facts are the evidence supporting the possible involvement of Ramsay, along with the Gardner security guard Rick Abath, and others, such as Brian McDevitt.

McDevitt lived just three miles from the museum, and had been convicted in an attempt to rob the Hyde Collection, an art museum in Glens Falls, NY, of a Rembrandt and other works ten years earlier.

In a Sixty Minutes interview, McDevitt said that he had no alibi for the robbery and a girlfriend of his at that time, Stephanie Rabinowitz said that McDevitt had asked her to lie, to say he was with her that night. In addition, McDevitt told Rabinowitz he was involved in the heist, she now says.

In addition to being interviewed on Sixty Minutes about his possible role in the Gardner heist, McDevitt was brought before a grand jury in 1994, regarding the robbery.

But in Netflix, This Is A Robbery Tom Mashberg said: “Very remarkable that between 1990 and 1997 there were very few stories about the crime. There was never, say, an arrest or a suspect being questioned. Bobby Donati, nobody ever had a chance to ask him any questions obviously.”

“Obviously”? Donati did not die until 18 months after the Gardner heist and was under FBI surveillance during at least some of that time, as he made collections from bookies and loan sharks for

the mob affiliated Vinnie Ferrara gang. Kurkjian too, in the same Episode 3 of

This Is A Robbery falsely stated that: “Between 1990 when the theft took place and around 1997 there was nothing.”

In Kurkjian's own book, he devotes six pages to a ransom note and a follow up note, the Museum received in 1994, which he said may have been

"the biggest disappointment, and the

closest [Gardner Museum Director Anne] Hawley feels the museum has yet come to recovering

the stolen art."

The Gardner heist occurred in 1990, but nothing happened that fits the

the current state sponsored narrative until 1997 so everything before that time, and much after it, is memory holed, by the likes of Mashberg and Kurkjian.

Real facts have gone unreported, or papered over with false facts by an iniquitous guild of access-driven journalists and

news media gatekeepers, who instead disseminate false narratives and suspect theories, originating from within the investigation itself.

These corrupted, crowd saucing manipulators exploit

the intrinsic sensationalism of the robbery, while investigators release information "in dribs and drabs," as WATD radio's Christine James observed,

in their efforts to

maintains narrative control of a fairy tale.

If ordinary hoodlums had actually pulled off the Gardner heist, we would know there names by now, or

the Gardner heist would have been long forgotten. But there is little opportunity for outsiders to fill in the blanks when the facts are so capably filled

by high budget productions, and journalists who traffic in deceit.

But while Rod Ramsay was a criminal, and a more experienced one than any of the individuals whose names have been tossed around by the news media as the actual perpetrators,

he was not an ordinary criminal. He was a soon to be incarcerated spy.

Another example is the highly promoted, highly reported on, reviewed and taken seriously Gardner heist productions was Last Seen Podcast

by the Boston Globe and a local NPR affiliate, WBUR, with Kelly

Horan serving in the role as senior producer. But while it was treated as a serious work of journalism, it was not, as Horan herself admitted three years later.

This arch-disseminator of Gardner heist myth, falsely claims on her Boston Globe bio page

that Last Seen Podcast "was named a top 10 podcast of 2018 by The Atlantic, the Financial Times, Stitcher, and other outlets.”

None of that is true, although it did garner quite a lot of attention, with dozens of local journalists endorsing it on social media at the time of its release

in September of 2018.

In 2021 and again in 2025 the same New York Times writer put it on a list of preferred podcasts.

One called "6 Podcasts About Making and Appreciating Art," and the other was "7 Podcasts About the Art of the Scam."

Last Seen Podcast (about a robbery) fits neither category, of the New York Times stories, but such is the clickbait power of the keywords [Gardner heist] that articles referencing Last Seen Podcast

and its Gardner heist subject matter, are

page-view powerhouses, real winners, though definitely not a winner for podcast listeners, looking for accurate information.

Last Seen Podcast does not even fit the category of “true crime,” as Horan herself acknowledged in an interview two years later:

"As someone who also has enjoyed a fair amount of pot boilers I knew that red herrings would work and

so my goal in structuring the entire [Last Seen Podcast] ten episode series,

the kind of narrative arc that I wanted to put in place was one where each episode would take you in deep inside a theory, you would meet the central characters of that theory and then you would leave that episode saying 'Aha! that's the one.' only to have the next episode come along and make you doubt that because that was my experience, the experience of reporting this was like whiplash. You know, 'This must be it.' 'No this must be it.' 'He must have done it. No he must have done it.'" —Kelly Horan

Horan’s “narrative arc,” however, was sold to the public as a serious work of investigative journalism:

“Iris Adler, Executive Director for Programming, Podcasts and Special Projects at WBUR

said that “the producers of Last Seen have obtained unprecedented access to case files, first-ever interviews and this podcast is the result of a year of investigative reporting to unravel the crime’s many mysteries.’”

It seems the Boston Globe and WBUR were given unprecedented access to case files, just so they could present an assortment of junk theories, “red herrings,” in the words of

the person who headed up the project, to present the public with disinfotainment. Last Seen podcast did not “unravel” any of “the crime’s many mysteries.”

A short time before its release one of the staff members on the project, Eve Zuckoff, now a city reporter for WBUR, tweeted out: "If you've spoken to me any time in the last 15 months, THIS is the secret @WBUR

and @BostonGlobe podcast I've been working on! Please SUBSCRIBE and get ready for SO. MUCH. MORE."

If WBUR and the Boston Globe were serious about unraveling mysteries they would not have made Last Seen Podcast in secret.

In 2016, Last Seen consulting producer Stephen

Kurkjian wrote that "secrets

that could lead to the whereabouts of the artwork remain hidden among associates, family members and friends of the thieves, and it's these

individuals who must be convinced to break their traditional code of silence." But the folloowing year when Last Seen Podcast began production, there was no

outreach through the mass media capabilities of WBUR and the Boston Globe. It seems inviting public participation was viewed more as an obstacle more than opportunity.

The public is just one more

scapegoat to explain away the pretend-failure of the FBI's pretend investigation.

Two years later, when the Netflix 4-part series, This Is A Robbery, was in the planning stages,

Kurkjian met with the Barnicle Brothers, who were heading up the production of Gardner heist series which was first released on Netflix in 2021.

Kurkjian's "major advice to them," he said, "was not to try to solve it, that if they tried to solve it, it would be too frustrating for them.

I told them I had tried since 1997 and I still know nothing about who did it, why they did it and most importantly, where the paintings had been stashed.”

Once again the "deep dive" was kept secret from the public until shortly before the release date, and limited to the same

to the same cast of journalistic characters, who either claim to know nothing, or speak in vaguest of terms about what the FBI believes, or lie about what "the FBI said."

Shelley Murphy: "The FBI believes the stolen artwork ended up in the hands of Guarente, a convicted bank robber with ties to the Mafia in Boston and Philadelphia who died in 2004."

Kevin Cullen: "The FBI believes the stolen artwork ended up in the hands of Guarente, a convicted bank robber with ties to the Mafia in Boston and Philadelphia who died in 2004."

Stephen Kurkjian: "The FBI believes that the heist was pulled off by local thugs who had been made aware of the museum’s poor security by fellow gang members.

Or they just lie. Tom Mashberg:

"In 2015 "the F.B.I. named two long-dead, Boston-area criminals,

George Reissfelder and Lenny DiMuzio, as the likely bandits." The "likely" bandits? In 2013, the FBI said they knew who the thieves were.

Geoff Kelly said "We know who did it." In 2015 Mashberg reported: Mr. [FBI's Geoff] Kelly showed me that Mr. Reissfelder and Mr. DiMuzio closely

resembled police sketches of the two men who had entered the museum." A month later in an email response to an inquiry by BosInno,

FBI spokesperson Kristen Setera said: “the FBI has NOT publicly identified the suspects involved in the Gardner heist.”

Mashberg's Stealing Rembrandts co-author, Anthony Amore, specifically stated in March of 2015 that "nobody named anybody."

In episode 4 of Last Seen Podcast, called “Two Bad Men,” Boston Globe reporter Shelley Murphy, one of the leading disseminators

of Gardner heist disinformation for over 30 years, acknowledged in Last Seen Podcast that: “All these theories are frustrating. For everything that points toward these particular suspects,” she said, “there’s something that points away.”

Frustrating indeed when a journalist spends decades of their career sourcing stories about the Gardner heist from people inside the investigation, who persist in casting aspersions on “suspects” for whom “there’s something that points away,” something exculpatory, something that excludes them from having actually been the actual Gardner heist robbers, effectively deflecting attention from other actual suspects like Ramsay, Abath, and McDevitt, despite strong evidence, and for whom there is little, if anything, “that points away."

It has not been so frustrating, however, that Murphy and The Boston Globe have ever done anything except assist in this disinformation operation,

anything except cooperate fully with it, disseminating the FBI’s dubious, ever-changing narrative, supported with false facts, while profitably propping

it up with sensationalist stories, a ten-part podcast, and a four-part Netflix series.

As full of inaccuracies and outright deceit as the Globe’s Last Seen Podcast, and The Boston Globe’s Gardner heist news stories generally,

is their four-part Netflix series This Is A Robbery This Gardner heist crockumenatary

was produced and directed by Colin Barnicle and his brother Nick, sons of the former Boston Globe columnist Mike "Blarneycle" Barnacle.

When Reader's Digest was set to reprint a 1995 Mike Barnacle Boston Globe column he wrote about a friendship between two young cancer victims, but was unable to substantiate the story.

"Blarneycle" was eventually compelled to resign from the Boston Globe in 1998.

Barnicle’s sons have done numerous projects for the Boston Red Sox, which is owned by the same people as The Boston Globe, John and Linda Henry.

Colin Barnicle was an intern for the Red Sox front office when he was a teenager in 2005. Linda Henry, The Boston Globe’s chief executive officer” was also an

executive producer

of the Netflix Gardner heist documentary. The Barnacle Brothers continue to prosper through their relationship with the Henry’s,

This year they were awarded a Sports Emmy for Outstanding Documentary Series in 2025, for their Netflix production about the 2004 Boston Red Sox.

In addition, four past and current Boston Globe reporters appear prominently in the series: Stephen Kurkjian,

Shelley Murphy, Kevin Cullen,

and Tom Mashberg. All four of these

reporters at the time of the documentary had been reporting about the Gardner heist for at least a quarter century.

In addition, all four of the journalists, who appear in the documentary, aside from archival footage, were current or former Boston Globe reporters.

This Is A Robbery was released in 2021. At that point Murphy and Cullen had worked at The Boston Globe for over thirty years. Kurkjian reported for the Globe for

over fifty years. He retired in 2007, but stayed on as a freelancer, covering the Gardner heist for the Globe for another 14 years, until 2021.

Although it had been a while, Mashberg recently wrote a freelance assignment for the Globe in October 2025, on the Louvre jewels heist,

and was employed by The Boston Globe as their

New York Bureau chief and then as a reporter for about three years in total, in the early nineties.

Along with Boston 25’s Bob Ward, these three Globe reporters (Mashberg, Kurkjian and Murphy) account for over ninety percent of the original reporting

on the Gardner heist the past ten years, a good deal of it insincere, false and misleading. Cullen covered the case for the Boston Globe in the days following the robbery, but has written little on the case in the last decade.

In 2015, Cullen expressed a good deal of skepticism about the Gardner heist investigation writing:

“On Thursday, federal authorities released a surveillance video showing a security guard letting a man into the Gardner Museum the night before it was robbed of 13 priceless paintings in 1990.

US Attorney Carmen Ortiz said officials hoped someone in the public might recognize the mystery man.”

“How could this crucial piece of evidence just be coming out, 25 years after the city’s most infamous unsolved crime? It seemed like either a breathtaking bit of incompetence by the FBI, or more evidence of the bureau’s reluctance to share information with law enforcement partners and the public.”

But by the time of Netflix's This Is A Robbery, Cullen had been won over. Since that 2015 column about the heist investigation,

Cullen had undergone his own Mike "Blarneycle" Barnicle type troubles.

After WEEI had questioned the truth of some of his past work, The Boston Globe conducted two reviews of Cullen’s past work, and while the veteran columnist was

given a three month suspension, he managed to keep his job.

The Boston Globe issued a statement on their findings in June of 2018:

“The reviewers found Mr. Cullen’s writing to be ‘among the most appealing that appears in the Globe -- precise, well observed and often standing up for the forgotten man and woman with profound effect.’

However, the review did find some problems, concluding

that “his columns at times employed ‘journalistic tactics that unnecessarily raise questions about his accuracy’ that ‘may open the door to

providing seriously

misleading information to the public.”

In other words, Cullen employed the very kind of dark-arts, inside journalism, that has been a central and sustaining feature, a cornerstone of Gardner heist news coverage

in the Boston Globe's news reporting about the Gardner heist case, since at least 2013, as well as

in its podcast, Last Seen Podcast, and in its documentary about the Gardner heist, This Is A Robbery.

By 2021, Cullen loved Big Brother. He was happy to help promote the government’s dubious narrative about the Gardner heist on the Boston Globe’s Netflix series on the case,

using those same “tactics,” in the series, which had put Cullen in hot water back in 2018, as one of the Globe's Gang-of-Four journalist in the series.

Cullen’s statements in Netflix This Is A Robbery, like those of his fellow Globe affiliated journalists, Murphy, Kurkjian, and Mashberg,

included some that employed “journalistic tactics that unnecessarily raise questions about his accuracy” that “may open the door to providing seriously misleading information to the public.”

In fact if you haven’t got game, you’re not part of the highly compensated Gardner heist guild of journalists who have appeared over and over again in all of these productions, and

whose bylines appeared almost exclusively in Boston Globe articles about the case for decades.

In Episode 3 of This Is A Robbery Cullen says, "It's really important to understand how organized crime works in the city of Boston," as if the documentary,

or anyone ever, had done anything like establish

that the Gardner heist was pulled off by local members of organized crime.

But Cullen is in his wheelhouse now: "You had the Irish faction in Southie. You had another another Irish faction in Charlestown bleeding [bleeding!] into Somerville," Cullen states,

laying on the Boston accent with a trowel, as if this Cullen guy isn't some dweeb from Melrose, but of duh streets.

"In the North End you had this sort of coalescing force called La Cosa Nostra," Cullen continues long after one of Blarneycle's boys should have shouted "Annnd CUT!."

'This thing of ours.' The Mafia," Wow! We're really getting into

some deep dive shit but, again, nothing whatsoever to do with the stated subject of this documentary, the Gardner Museum heist.

The newest member of the gang that wouldn’t report straight is Kelly Horan. In October of 2025 Horan left her job as the Globe's Assistant Ideas editor, after six years.

So far, Horan has enjoyed a mere seven-year career as a Gardner heist dissembler, and red herring disseminator. Can her gift for lying with a straight face

propel her onward in the Gardner heist media landscape? Currently she is "writing a book set in Second Empire France." Uh-huh. We all know what that is. It will be a "pot boiler" no doubt.

In 2025, the Boston Globe bought Boston Magazine, which was already an established channel of Gardner heist disinformation.

In 2024, the former editor, Carly Carioli, falsely reported in 2024

that on Sunday, March 17, [Myles] Connor will once again take center stage when he appears at the Regent Theater in Arlington, in conversation with Gardner Museum security

director Anthony Amore and Myles’s longtime manager and collaborator Al Dotoli, for the premiere of Rock n’ Roll Outlaw: The Ballad of Myles Connor, a new documentary that examines Myles’s incredible backstory—and what he may know about the Gardner heist.

But there was no documentary shown that day and there is still no documentary that has ever been released.

A year later though, there was a cheesy book about Connor, “The Rembrandt Heist: The Story of a Criminal Genius, a Stolen Masterpiece, and an Enigmatic Friendship” by Gardner Museum’s

security director Anthony Amore.

Just how enigmatic the friendship between the Gardner Mueum's head of security, Amore,

and Connor, whom Amore described in 2013 as a "charlatan" and a "huckster." (Time: 1:24:00)

is a question for the Gardner Museum’s trustees to decide.

What Amore finds interesting or special, an investigator forming a friendship with a criminal, is in fact all too common, and generally regarded as an occupational hazard of investigative work,

as was seen with the relationship between two FBI agents John Connolly, and John Morris with Whitey Bulger.

In speaking of Myles, Amore said: "From the handshake we just hit it off. It was weird."

Was it though?

"We just have this appreciation.

I think we both have this appreciation for art that I think is unique from the vast majority of people. (It's "unique" all right.)

And somewhere in the middle between good and evil, you have that gray area where Myles and I meet."

That's what they all say, although generally through their defense attorneys.

In 2014 Amore said of Connor: "He is one of these guys who committed every type of crime you can imagine. Make a list. Brainstorm on crimes. He can check off every box. You name it. he's done it,

a real bad guy." But now in the title of his book, Amore

calls Connor a criminal genius. If Connor was such a criminal genius, we would never have heard of Myles Connor and he would not have spent most of his adult life in jail, in prison, or on the lamb.

Connor is the kind of criminal genius who does a long stretch in prison for selling art, burglarized from an elderly widow, to an undercover FBI agent,

and then 15 years later does another long stretch in prison, for selling art stolen from the same elderly widow the same day,

to another undercover FBI agent. According to Connor's book, The Art of the Heist,

the agent posed as an Italian mobster named "Tony Graziano," with a hankering antique Simon Willard grandfather clocks.

Genius!

Ex-con Connor the con artist is a regular also on the Globe's Gardner heist podcast, and docuseries circuit.

As Amore said, Connor is a huckster, so having Connor on to speak of things that

are either not corroborated, or flatly contradicted by the public record, is a natural fit for these faux-true crime productions.

Connor helps reinforce the false narrative that Donati was involved in the Gardner heist, by claiming that Donati was one of the crew who burglarized

the Woolworth Estate in Monmouth, Maine with him. It was on the Saturday of Memorial Day weekend in 1974, he wrote in his memoir.

Whoops! Donati was sentenced to state’s prison only days earlier that very week.

Connor also likes to describe how he and Donati cased the Gardner Museum. In his book he says it was in the summer of 1975, which happens to be another time when

Donati was incarcerated. This time at

the Deer Island House of Correction.

In his book Connor wrote that he and Donati “found ourselves strolling through the lush courtyard garden,” at the Gardner Museum that summer.

What Connor claims

is that while he was a fugitive from justice, and just a few months after he says he personally grabbed a Rembrandt off the wall at Boston's Museum of Fine Arts, although he doesn't

fit the description police released to the public, which is just one-third

of a mile away from the Gardner Museum, Connor who, Amore claims was Very popular, Myles and the Wild Ones, He was a huge star in Massachusetts. He's in the Massachusetts Rock 'n' Roll Hall of Fame.

No mean feat since the Massachusetts Rock 'n' Roll Hall of Fame doesn't exist and never has.

Yet despite being recognizable due to his status as "a rock star," as well as because of his criminal escapades,

Connor claims he went for a stroll in the Gardner Museum, while he was a fugitive from justice, skipping out on his his trial, for trying to sell stolen art to an FBI undercover agent.

Connor is not only ill suited for the role of criminal genius in fact, but in his own fictional accounts of his exploits.

This go-along-to-get-along (quite comfortably one might add) news coverage of whatever questionable, self-contradicting claims the Gardner heist investigators, and their minions,

are promoting on any given heist anniversary, or any other time, is just one of the many facets of the Gardner heist story, which point to there being more to this case than

a simple robbery investigation, something that overlaps with something like the strange case of convicted spy Roderick James Ramsay.

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part Two)

|

By Kerry Joyce