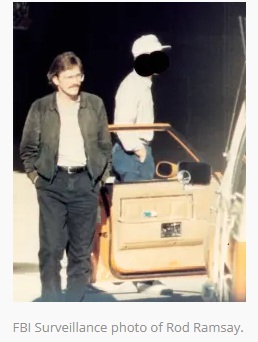

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part Five)

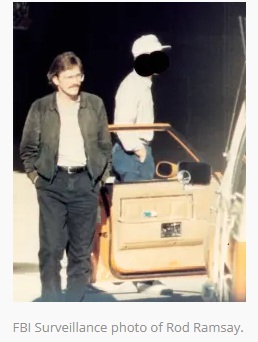

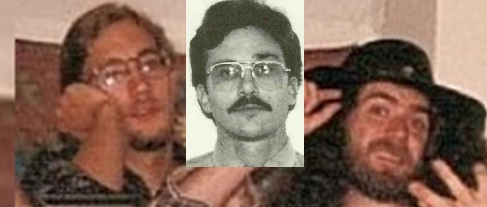

Pictures of Gardner heist eve video visitor

March 17, 1990 (left) and Rod Ramsay in Tampa, FL after his arrest on espionage charges

on June 7, 1990 (right)

Pictures of Gardner heist eve video visitor

March 17, 1990 (left) and Rod Ramsay in Tampa, FL after his arrest on espionage charges

on June 7, 1990 (right)

As desperate as the Gardner heist would have been, even for someone as desperate as Ramsay, it could at least serve as an opportunity to strike a blow against the city of Boston,

where his past misdeeds, he may have realized, or suspected, had come to light, as well as the government, which had used him.

Ramsay, the smartest guy in the room, who played at being a master archcriminal with Clyde Lee Conrad, like it was Dungeons and Dragons, for a couple of years,

might have suspected that while he thought he and Conrad were playing the U.S. Army, it was he and Conrad who were being played all along.

According to a 2022 article in Daily News Hungary, Lt. Col. István Belovai, a Hungarian Strategic Military Intelligence Service officer,

first got in contact with the CIA in 1982, to inform the Americans about the activities of the

infamous Conrad spy ring, one of the most damaging

espionage operations ever against NATO." Ramsay did not arrive in Germany until 1983.

(American and Western news media) place Belovai's dealings with the CIA beginning in 1984.

Navarro too, in Three Minutes to Doomsday, suggested that the investigation into the spy ring preceded Ramsay’s arrival at the Eighth Infantry Army Headquarters.

After quoting Ramsay as saying that he met with Conrad in Boston, in “maybe the spring of ’86,” he next writes that Conrad had been in WFO’s [the FBI’s Washington field office’s] sights for years by then.

The 1999 book Traitors Among Us by Stuart Herrington pushed back the timetable of the Army's awareness of the Szabo/Conrad spy ring back even further. Herrington wrote that

in 1978, six years before Ramsay set foot in Germany,

that CIA sources in Moscow advised ominously of “a Hungarian penetration that was regarded as the most lucrative espionage success in Europe since the end of World War II.”

CIA officials, realizing the importance of their agents' warnings, brought the grave news to the Department of Defense in 1978.

The agency tip led to what would ultimately become the longest-running, most sensitive, most tightly compartmented, and costliest counterespionage investigation in history. If the agency's spies were correct, NATO's ability to defend Western Europe against the Soviets and their Warsaw Pact allies was in jeopardy.”

Only after the investigation had been ongoing “for years,” was Ramsay assigned G-3 [War] Plans of the division headquarters, placed in the exact same position Conrad held, when he was recruited by Zoltan Szabo, whose former position Conrad then held.

In courtroom testimony, Navarro described Ramsay as someone with a high IQ, who spoke Japanese, Spanish and German. He was also said to have a remarkable gift of near total recall of whatever he read.”

In addition as someone who graduated high school from the same military boarding school as Donald Trump, Ramsay would have had little trouble conforming to the rigors and traditions of military life, which would have reassured the senior NCOs and commissioned officers above him.

At the same time, Navaro also testified that before joining the Army on November 17, 1981, Ramsay had robbed a bank in Vermont, and while working as a security officer in a hospital, had attempted to break into a safe.

For Conrad to bring someone into his espionage operation, Navarro told Ramsay in one interview, he described in his book, “It had to be someone he trusted, someone who was really smart, someone who wasn’t scared to push the envelope, someone as smart as Clyde himself.”

“That would make perfect sense, wouldn’t it?”—with emphasis on the word “perfect,” Navarro wrote Ramsay replied.

A little bit too perfect, however, and Ramsay's reply suggests it may have dawned on him just how very a-little-too-perfect it all was.

As Rod’s mother said to agent Navarro, “Rod was assigned to that job, Mr. Navarro. He didn’t seek it out."

The odds of someone smart enough and criminal enough (an actual bank robber) to be relatable to Conrad,

and to wind up assigned by the Army to work directly under him, at the site of his decades long espionage operation,

as a records custodian for some of the Army's most top secret documents, was greater, much greater, than a one in a million shot.

Continue

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part Four)

For twenty months, after having implicated himself in espionage, Ramsay had been free to come and go as he pleased.

There was not even any surveillance on him of any kind for over a year, or so Navarro stated in his book:

For a year Ramsay was seemingly left to his own devices to try to develop a plan to extricate himself from this seemingly hopeless predicament.

Perhaps counter intelligence operatives were interested in what Ramsay would do in such a desperate situation, and sought to find out whom he would contact, by keeping him

under surveillance, but in secret, even from agent Navarro.

In a scene in the fictional TV series The Americans, a Russian spy character named Nina Krilova, remarked to one of the FBI's spy-catchers in an episode:

“What do you want with us? With Arkady and the others at the Rezidentura? Do you want to put them in jail? That's how policeman thinks, not how spies think.

We want everyone to stay right where they are, and bleed everything they know out of them forever.”

So it might well have been with Ramsay. The FBI’s desire to gather information from him, including information he would not readily

give up voluntarily was a higher priority than prosecuting him for espionage, especially at the beginning of their engagement with him.

About a month after the start of Agent Navarro's second round of meetings with Ramsay,

ABC News reported on October 30th, 1989, that Conrad’s recruits continued to work for him back in the United States,

illegally exporting hundreds of thousands of

advanced computer chips to the Eastern Bloc, through a dummy company in Canada.

Ramsay admitted to the FBI that he was the source of that ABC News story, but said that he and Conrad had only discussed illegally exporting chips to the Eastern Bloc, during

their brief meeting in Boston, in January of 1986, but the

project, Ramsay claimed, had never gotten off the ground.

The two spies

had never followed through on their plan to illegally export the computer chips, he insisted. “That [ABC] producer, Jim Bamford, he kept bothering my mother. She was getting very

upset. I thought if I just gave him this one little story, some bullshit, he would go away,” Ramsay told Navarro.

In that way Ramsay acknowledged that he and Conrad had at least engaged in the planning stages of illegal acts inside the United States

that threatened national security.

Facing the possibility of decades in prison, or even life, Ramsay was an individual in desperate circumstances, but one with a sharp and experienced criminal mind

with which to come up with the means to possibly save himself.

The only alternative to abjectly submitting to his fate in the federal criminal justice system, with the weak cards he was holding, would have been

to come up with some different cards, a plan, something big, given the kind of manhunt that he, as one of the most prolific spies in American history would be up against, if he simply

fled.

Ramsay would need a caper big enough to make such a manhunt something that could be either overcome or unnecessary, a plan where he would be negotiating from strength and could strike some kind of a deal. At the very least it would have to be able to help make his life more comfortable while he was inside prison, and perhaps after he got out, with a shorter sentence possibly, as well.

"Over 25 years, so many names have been thrown into this [the Gardner heist case],"

Kurkjian said in 2015. But none of those so many names included Rod Ramsay, and none had the kind of motivation, the desperation, or the kind of extensive criminal background that

Ramsay had, which matched up so well with pulling off the Gardner heist. Nor did any of those "so many names," like Ramsay's, have the need for secrecy that

the government might deem necessary, if it were a spy who robbed the Gardner, and not some local hood, whom the FBI never quite got around to interviewing.

Continue

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part Three)

"Law enforcement sources said that the [Gardner heist] suspects'

movements are under close scrutiny by federal agents, including one suspect who was under surveillance during a recent arrival at Logan Airport."

"Law enforcement sources said that the [Gardner heist] suspects'

movements are under close scrutiny by federal agents, including one suspect who was under surveillance during a recent arrival at Logan Airport."

—Elizabeth Neuffer, Page 1 Boston Globe May 14, 1990

Meanwhile, on short notice, the FBI's field office had received instructions to seek out an interview with Rod Ramsay on the same day

that Conrad was placed under arrest:

"Anytime after 0400 hrs Zulu [eight o'clock a.m. in Florida and two o'clock p.m. in Bosenheim, West Germany] 8/23/88, you are to locate and interview Roderick James RAMSAY, last known

to be living in Tampa, Florida, regarding his knowledge of or association with Clyde Lee CONRAD while stationed at 8th ID, Bad Kreuznach, West Germany: service years 1983—85. INSCOM [Army Intelligence]

will liaise and assist: locate, interview, report."

Although the appearance of federal agents at his door that day was unexpected, Ramsay was not unprepared, and may not have been caught entirely off guard.

Conrad had told Army undercover agent, Danny Williams, months earlier, how

he suspected he was under investigation, and claimed to have warned his espionage confederates, though not the Hungarians, of this looming threat.

Toward the end of their first meeting, FBI agent Joe Navarro asked Ramsay if Conrad had ever given him

anything. With that prompting, Navarro wrote, in Three Minutes to Doomsday, Ramsay

took from his wallet a mysterious slip of paper with a hand-written telephone number on it, which Conrad had told him to call, if he had to reach him, Ramsay

told Navarro.

Navarro carefully placed the slip of paper into an envelope, and brought it back to the FBI Tampa field office.

An FBI lab determined that the note given to Ramasay was written on a water soluble paper of a kind sold in novelty shops. It was known to be

favored by Eastern European intelligence services, as well. The paper

dissolved instantly, when exposed to any liquid, such as saliva, making it useful for rapid disposal and destruction of sensitive information in an emergency.

The telephone number was quickly identified as one belonging to the Hungarian Intelligence Service, by one of the other members of Conrad's espionage gang,

Imre Kercsik, according to Navarro.

A Hungarian born physician, and Swedish national, Kercsik served as a courier for the spy ring

and was arrested, along with his brother, also a medical doctor,

soon after Conrad. Unlike Conrad, the two brothers cooperated with investigators. Four days after Conrad's arrest, and after the FBI's first interview with Ramsay,

the New York Times reported on the front page that the Kercsik brothers were under arrest, admitted working for the Hungarian intelligence service,

and that Sandor Kercsik "told Swedish officials that he first met Clyde Lee Conrad in 1974."

"Mr. Conrad is potentially a more valuable source of information," the article also reported,

"since he was responsible for obtaining the highly classified documents and could describe exactly which secrets were compromised."

But Conrad never did cooperate, which made the interviews with Ramsay, Conrad's right hand man, with "a near photographic memory,"

as Navarro had testified, even more important.

The slip of paper given to Navarro by Ramsay represented hard evidence of Ramsay's personal involvement in espionage.

Continue

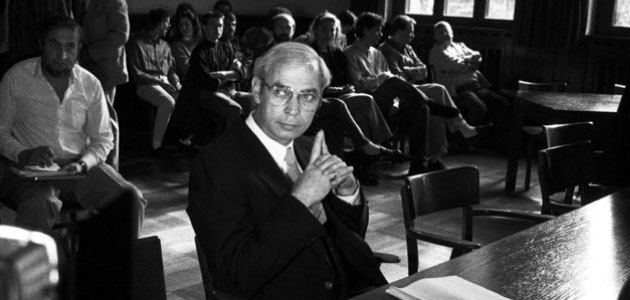

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part Two)

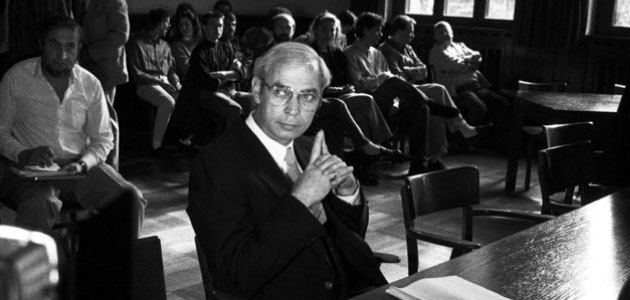

Clyde Lee Conrad on trial in a West German courtroom. Conrad was convicted on June 6, 1990

for his espionage activities while serving there on active duty in the U.S. Army,

and after he retired from the Army as a resident of West Germany

Clyde Lee Conrad on trial in a West German courtroom. Conrad was convicted on June 6, 1990

for his espionage activities while serving there on active duty in the U.S. Army,

and after he retired from the Army as a resident of West Germany

A Boston native, Roderick Ramsay was a member of the Szabo/Conrad spy ring

while stationed at the Army’s Eighth Infantry Division Headquarters in Bad Kreuznach, West Germany from 1983 to 1985, according to official accounts.

In an interview, Ramsay said his "personal involvement in the conspiracy

was from the spring of 1984 until January of 1986," when he met with the spy ring leader, Clyde Lee Conrad in his hometown where he was living at the time, Boston, MA.

Ramsay's criminal career, however, did not begin with espionage. After his arrest, in June of 1990, the Washington Post reported

that Ramsay had robbed a bankin Vermont, and that

while working as a security guard in a hospital, he had attempted to break into a safe," according to the testimony of FBI agent Joe Navarro, at his detainment

hearing the day after he was arrested on June 7, 1990.

The Vermont bank robbery took place on August 28, 1981, just eleven weeks prior to his enlisting in the Army,

and at a time when the former Northeastern University college student was living just three miles from the Gardner Museum.

In his book, Three Minutes To Doomsday, Joe Navarro recalled how Ramsay in one of his forty interviews with him in an official capacity,

had told him about the "the bank he and some pals robbed."

Ramsay lived with a high school friend in the Whittier Place building of the Charles River Park luxury apartment complex, overlooking Boston's Storrow Drive, and the Charles River

near the Boston Museum of Science.

The roommates had both attended New York Military Academy, a boarding school whose famous alumni include Donald Trump, John Gotti as well as the composer and lyricist Stephen Sondheim.

Twenty four years after the robbery, on August 28, 2014, Stephen Kurkjian, author of Master Thieves, about the Gardner heist case, sent an email to Joe Navarro, at 2:44 a.m.,

which he forwarded to me, a couple of days later.

At one point in the email, Kurkjian observed that "the two roommates [Ramsay was one] look somewhat like the sketches of the two thieves."

The exchange with Navarro occurred six months before Kurkjian's book Master Thieves, came out, coinciding with the 25th anniversary of

the Gardner heist robbery. The already completed manuscript would not include anything about "the two roommates," the long time Boston Globe reporter

had made inquiries about to Navarro, in the early morning hours of his 71st birthday.

At the same time that Kurkjian's book came out, it was announced by the author and ghost writer Howard Means, that "This book still needs to be written, but

from the April 13, 2015, VARIETY: George Clooney and Grant Heslov’s Smokehouse Pictures has picked up the film rights to Joe Navarro’s “Three Minutes to Doomsday.”

That book came out two years later, but there was nothing in it linking Ramsay to the Gardner Museum, or the university he attended, the apartment complex he lived in,

or the hospital he worked at as a security guard only a short distance from the museum.

Two other friends of Ramsay, who were also recent graduates of the New York Military Academy lived nearby at Charles River Park as well. The four

friends all attended Northeastern University. With the exception of Ramsay, the four friends were from well-to-do families, the sons of successful self-employed fathers.

"I'm not like them," Ramsay would remark sometimes bitterly.

The luxury apartment complex was built on 43 acres of what had formerly been the West End, a working class neighborhood situated on prime real estate. The neighborhood was razed in 1958, displacing some 2500 families, in the name of "urban renewal." Among

those who grew up in what the government deemed a "blighted," tenement neighborhood, were actor Leonard Nimoy and the painter Hyman Bloom.

Using Ramsay's Whittier Place apartment, as a long distance staging area, three men,

two armed with shotguns, robbed the Howard Bank in Barton, Vermont,on August 28th, 1981.

A fourth man in a black,

1973 Oldsmobile

Toronado, which had been reported stolen in Massachusetts a week earlier, waited outside with the engine running. The bank was a three hour drive from Boston,

and only 22 miles from the Canadian border.

The robbers came away with about $10,000, according to news reports. Ramsay, who was only 19 years old at the time,

was said to be the mastermind of this seemingly successful robbery.

With his share of the money, Ramsay quickly left Boston. Travelling to Japan, and then to Honolulu, he enlisted in the Army in Hawaii when the money ran out.

Eighteen months later, Ramsay arrived at the military duty station that would seal his fate, the U.S. Army's Eighth Infantry Division Headquarters in Bad Kreuznach, West Germany.

was with a top secret security clearance "assigned to safeguard sensitive military plans," at what was

ground zero for "one of the largest espionage conspiracies in modern U.S. history."

In court shortly after his arrest, Navarro described the 29 year old Ramsay as a "career criminal." Yet Ramsay had managed to receive a top secret military security clearance,

when he was assigned to work under Conrad as assistant classified documents custodian of the G-3 [war] plans section.

Continue

Convicted spy Rod Ramsay as a potential Gardner heist suspect (Part One)

Though his name has never been raised with the public as a Gardner heist suspect by either investigators or the news media, Roderick James Ramsay, a former Boston resident, arrested on espionage charges in Tampa, FL, on June 7, 1990, just ten weeks after the robbery, is certainly someone who remains worthy of consideration. Ramsay was convicted of espionage two years after his 1990 arrest and spent over a decade in prison after his conviction in 1992.

The Boston Globe, New York Times and other news media long ago abandoned hard reporting on the Gardner heist case in favor of “conjecture based on a

theory,” mutely disseminated by government officials

and their surrogates, like former FBI Gardner heist lead investigator Geoff Kelly, who in retirement has updated his narrative

(changed his story). He now claims that the security guard Rick Abath was indeed in on the robbery, after publicly suggesting otherwise

on numerous occasions for over twenty years. Kelly, who has a book on the Gardner heist investigation coming out in 2026, bases his conclusion on information known to investigators the first week; that the Museum security system did not record anyone going into the Blue Room gallery,

where Manet’s Chez Tortoni was taken, with the exception Abath, who was recorded entering the gallery twice.

As Kelly himself said on CBS Good Morning ten years earlier, in 2015: "Someone went into the

Blue Room that night, and the only one that went in that room that night was the security guard [Rick Abath], according to the motion sensor printouts."

But when Abath refused to speak with CBS Good Morning, and said publicly he was not doing anymore interviews, the FBI and its surrogates reverted to their false narrative that Abath was tricked into letting the thieves in.

By April of the following year, in 2016, the Gardner Museum’s secuirty director Anthony Amore, who is also

the FBI’s chief public relations surrogate on the case said:

“We have nothing to point at to say that he [Abath] was involved.”

Continue

The Gardner Museum's Disinforming Ad Campaign (Part Two)

False Facts In The Gardner Museum Audio Walk

Link to (Part One)

Text taken directly from the Gardner Museum Audio Walk appears in blue.

Amore: Thank you for joining me [Gardner Museum Security Direct Anthony Amore]

as we retrace the thieves’ steps—and find out what really

happened—on March 18th, 1990.

Gardner Museum "Heist" Ad August 20, 2025

This museum audio description of the Gardner heist does not describe "what really happened."

There are numerous false facts, and unsubstantiated claims

presented as facts, which showcase the museum's willingness to support the FBI's disinforming false narrative about the

Gardner heist, which seeks to explain the Gardner heist case as "the handiwork of a bumbling confederation

of Boston gangsters and out-of-state Mafia middlemen, many now long dead," while protecting Abath so long as he kept his mouth shut.

Silencing Abath had formerly been a top priority for the FBI, until he died in 2024. Now after twenty years of claiming that

Abath was not a suspect, the Boston Globe is reporting that the former Gardner heist lead investigator, Geoff Kelly is convinced that Abath was involved.

The museum audio also glosses over the utter lack of

any tangible basis for concluding there had ever been any actual investigation of the Gardner heist, as the term is generally understood,

or anything other than

the blocking of an investigation into what actually happened, by the FBI.

Let's begin. There was no equipment in the Gardner Museum in 1990 that could retrace the thieves' steps. There were electric

eyes in the door jambs of the galleries, which recorded when someone entered or exited some of the galleries and other

spaces in the museum.

This could be chalked up to a metaphorical description, but it has been repeated so many times over 15 years that

it gives an added measure of knowledge, and authority to what is known and being shared with the public. Most people

who have spent time learning about the case are surprised to learn that there was no equipment literally tracking the steps

of the thieves. At no time has anyone involved in the investigation made any reference to the electric eyes in the door jambs,

in speaking publicly about the case.

In 2009 the Boston Herald reported, "The thieves shut off a printer that spit out line-by-line data on any alarms

that would be triggered by movements in the museum.

But the computer hard drive still recorded the thieves steps in the galleries."

No equipment "recorded their footsteps."

Amore: Two security guards were on overnight duty, as was typical. They’re stationed at a security area

downstairs.

In this case where the security guards were "stationed," and where they were in fact located were two distinctly different things,

when the thieves entered the building.

One of the guards was indeed located in the security station. He alone made the decision to let the thieves into the building.

At some point later, that guard called the other guard on

a walkie talkie, and asked him to return to the security station, he says, as he had been instructed to do by one of the

thieves.

"Inside the Venetian-palace-style building, two young watchmen were on duty.

One of the security men was seated at a guard’s desk in an office next to a door facing the Palace Road side entry.

The second guard was doing lengthy rounds within the compound,"

the Boston Herald reported in 2009. The guard was only ten seconds away on the stairs near the security station, when he was called

by the guard inside the security station, Rick Abath.

Continue

The Gardner Museum's Disinforming Ad Campaign (Part One)

For over two months now, at least, the Gardner Museum has been running Google paid search ads with keywords regarding the Gardner heist, covering an area at least 50 miles from the museum and out of state. Last month, for example, I entered: [gardner rick abath] into Google, and my search results included an ad for the Gardner Museum.

The landing page for the ad was a page on the Gardner Museum website with the header "Gardner Museum Theft: An Active and Ongoing Investigation."

Frequently there are large, what are called half-page ads, and two ads

on the same page in the Google search results. The ads are probably very inexpensive, since Google ad prices are based on an auction system, and no

one else is buying ads for the keywords [gardner heist], it seems.

But the Gardner Museum is spending some money to bring people to a particular page on their website about the robbery.

What is the point, exactly? The Gardner Museum's

"theft" page is consistently at or near the top of Google search results for "Gardner heist," for free as part of the

natural search results delivered by

the Google algorithm. So if you were to put [gardner heist] into Google, you stand a chance of Google returning results

with three of the top ten results being the Gardner Museum.

Gardner Museum "Heist" Ad June 22, 2025

Without

scrolling, the only thing displayed on the ad's landing page, which you arrive at if you click on the ad,

is a large photograph of the Gardner Museum Dutch Room. Then, further down is some dodgy history

about the theft, and finally, some pictures of the stolen art at the bottom of the page.

The ad itself has some false information in it, too. The headline includes: "See The 13 Stolen Works."

Apparently, the Gardner Museum assumes that everyone knows that none of the art has been recovered,

and that you can't see any of it. All you can see are photographs of the stolen items on this webpage, which is not the same thing.

There is nothing special about the photographs. These same images can be found in a lot

of places.

The ad also invites visitors to retrace the steps of the thieves. This, too, is false. There was no equipment in the

Gardner Museum at that time that recorded the steps of the thieves, or movement of any kind, most importantly

within any gallery.

Further down on the webpage, the Museum asserts that

"the facts are these: In the early hours of March 18, 1990, two men in police uniforms rang the Museum intercom and stated

they were responding to a disturbance.

This is not a fact. This is an uncorroborated and

updated account of what happened, taken from Rick Abath, the security guard who let the two thieves in. There are no witnesses

to what Abath claims were the words exchanged between him and the thieves he allowed in, except for the thieves themselves,

and The Boston Globe reported in March of 2025 that the Gardner

heist's own lead investigator for the previous 22 years, Geoff Kelly, is "convinced" that Abath was one of the Gardner heist thieves.

Abath is hardly someone whose statements can be accepted as "the facts."

Continue

Double Speak

Double Think

Double Plus Ungood For You

The time the FBI ran two condtradictory Gardner heist narratives on the same

day in the same place, in front of the entire national media and nobody said jack about it.

By Kerry Joyce July 2, 2025

On the anniversary of the Gardner Museum heist in 2013, the FBI held a press conference,

where the head of bureau's Boston office famously

announced that the FBI had identified the Gardner heist thieves.

"FBI agents had developed crucial pieces of evidence that confirmed the identify of those who entered the museum and others associated with theft,

but that "because the [23-year-old] investigation is continuing it would be 'imprudent' to disclose their names or the name of the criminal organization,"

With Soviet era servility the Boston Globe began their front-page coverage of the story by reporting that:

"Federal investigators, in an unprecedented display of confidence that the most infamous art theft in history

will soon be solved, said Monday that they know who is behind the Gardner Museum heist 23 years ago and that some of the priceless artwork was offered for sale on Philadelphia’s black market as recently as a decade ago."

Eight days later, however, the Boston Globe, in an unsigned editorial, contradicted the Boston Globe's own characterization of

the press conference in their reporting.

"Whether this is an expression of confidence

or desperation is anyone's guess," they wrote.

Twelve years and over a hundred Boston Globe newspaper articles later, in addition to a ten-episode Boston Globe podcast,

Last Seen

and a four-episode Boston Globe Netflix documentary (This Is A Robbery), and absolutely nothing to show

for it in terms of progress in the FBI's investigation,

what can we conclude? Was this FBI announcement,

an act of desperation

or of confidence?

There were definite signs of desperation by the FBI at the press conference. Their

progress report's most recent and definitive date concerned

the possibly sighting of some stolen Gardner art "about ten years ago." Why the ten-year wait?

Subsequent stories said the information had been brought to the FBI's attention three years earlier. OK then,

why the three-year wait?

Continue

History's Worst Draft

By Kerry Joyce June 23, 2025

The Big Lie The Boston Globe won't stop telling about a key historical fact of the FBI's

Gardner heist investigation.

"Oceania had always been at war with Eastasia" —George Orwell "1984"

14 times

in the last ten years, and as recently as March 18, 2025, the Boston Globe has falsely and deceitfully reported that:

"In 2013 the head of the FBI’s Boston office [Richard DesLauriers] said at a

press conference that the agency knew who had pulled off the robbery and that both men were dead,"

as Kurkjian put it in

the December 27, 2015 edition of the Boston Globe.

In fact, the head of the FBI's Boston office did not say this in 2013.

The FBI changed their story. They did not claim that

the thieves were dead until two years later. What DesLauriers suggested

at the 2013 press conference was that the Gardner heist

thieves were still alive, and

still in control of the art as recently

as 2003.

For proof that the Boston Globe backdated the FBI's claim about the thieves being dead,

look no further than the Boston Globe's own news coverage on the day

of the March 18, 2013 FBI press conference.

And at the many references to the 2013 press conference, which appeared in the Boston

Globe prior to the August 7, 2015 Associated Press story, none which included anything about

the Gardner heist thieves being dead.

Continue

Copyright © 2025 All Rights Reserved kerry@gardnerheist.com

|

“The authentic and pure values — truth, beauty and goodness — in the activity of a human being are

the result of one and the same act, a certain application of the full attention to the object.” Simone Weil

"Public enlightenment is the forerunner of justice and the foundation of democracy. Ethical journalism strives to ensure the free exchange of information that is accurate, fair and thorough.

An ethical journalist acts with integrity." — Society of Professional Journalists Code of Ethics

"I get the feeling that when you rely upon the FBI as a source

then you lose your ability to tell the truth about that source. Maybe had [Boston Globe reporter Kevin] Cullen and and [FBI agent John] Connolly not been so close much of

this would have not happened. The continuing flow of information is dependent upon the continuation and maintenance of the good

relationship. Once in bed with a government agency it.s hard to crawl out." — Career Prosecutor, and former Deputy District Attorney for Norfolk County, Matt Connolly

"Sensationalism can override the truth of a news story." —Rick Abath 2015

"We’re really looking for what we describe as 13 perfect fugitives."

—Geoff Kelly, FBI Gardner heist lead investigator (now retired) and now author, and

a partner at Argus Cultural Property Consultants, from the podcast Inside the FBI June 23, 2023

Gardner Heist Aftermath

Post-Truth Makes Camp in the Athens of America (Part One)

Read what the fuss is all about and the orginal

Read what the fuss is all about and the orginal

"kooky manifesto" comment here.

It Doesn't Add Up

1. "We have identified the thieves, who are members of a criminal organization

with a base in the Mid-Atlantic states and New England." Richard DesLauriers FBI Boston SAIC March 18, 2013

+2."I can't tell you specifics about the [Gardner Heist] thieves and what I know from them. All I can say about them is that they cannot lead us to the paintings today."

Anthony Amore Gardner Museum Security Director November 12, 2014

+3. The two individuals that took them and committed this crime are currently dead." Peter Kowenhoven FBI Boston Assistant SAIC March 18, 2015

+4. "In 2013 the head of the FBI’s Boston office said at a press conference that the agency knew who had pulled off the robbery,

and that both men were dead." —Stephen Kurkjian, Boston Globe December 27, 2015

Gardner Heist FBI

Quote of the Day

"The FBI does not generally rely on private investigatators when it is assisting

in art-theft investgiations. However, agents will accept information from any source."

FBI (Boston) spokesman Paul F. Cavanaugh March 20, 1990.

Gardner Heist / Art Recovery

Can anyone tell me the name of one suspect,

interviewed by the FBI in the year following the Gardner heist, besides

William Youngworth. Asking for a city.

Seven years later, Youngworth made the most public and tanglible offer to return the Gardner art, and was pursued by the Gardner Museum,

for years afterward in the hope of facilitating a return.

"While it may not point to a conspiracy, I remain intrigued as to how the FBI

could have muffed the investigation at several key points.

Why not focus on [museum guard] Abath more widely and intensively at the probe’s outset?"

Stephen Kurkjian Research Gate March 2019

"We know who did it."

—Geoff Kelly, FBI Gardner heist lead investigator (now retired) December 4, 2013

"We really have a good idea of how we think the heist went down back in 1990

and where the art work moved over the years, and individuals, who were responsible for the theft and may have

had some involvement... But again, I always temper that by saying that we could be wrong."

—Geoff Kelly, FBI Gardner heist lead investigator (now retired) June 23, 2023

"We know who did it."

—Geoff Kelly, FBI Gardner heist lead investigator (now retired) October 21, 2025

"The Gardner case followed none of the conventions and protocols of a typical investigation."

—Geoff Kelly, FBI Gardner heist lead investigator (now retired) January 28, 2026

"I began to explain how I had become involved in the case, when [former FBI Gardner heist investigator

Robert] Wittman interrupted me, saying as he said in later interviews. 'Everything you know about the case, it’s all bullshit.

I can tell you that right now. It’s all speculation bullshit.' I stumbled for a moment.

'Is there hard stuff out there?' 'I can’t get into it,' he said. 'But I’m telling you this because

I like you. You seem like a nice dude. You need to wait a little while. If you want to do a history of speculation, that’s fine.'

"I asked him about some of the people who’ve been accused of being behind the heist over the years, people like David Turner and Bobby Donati and George Reissfelder."

'Nope,' he said. 'Don’t know them.'” Ulrich Boser The Gardner Heist 2009

"All I offer are theories. I don't know where these paintings are. This is just a mystery. So all the people who have joined us today, you, any theory to some degree is just as valid as what I have.

Really what I'm saying here is that the mystery is kind of the core of this

and it is what attracts people." —Ulrich Boser April 24, 2025

I told them I had tried since 1997 and I still know nothing

about who did it, why they did it and most importantly, where the paintings had been stashed.” —Stephen Kurkjian May 27, 2021

Repeat art fraudster arrested for stealing Courbet painting The Art Newspaper November 27, 2025

“The art world needs a database of people who have defrauded someone, who have not paid their debts or should not be traded with. A database like that would be a major deterrent to these kinds of crimes, getting the art trade closer to the standards of other industries, like banking and insurance.”

Four more arrested in $102M Louvre jewel heist, Paris prosecutor says

The two men and two women in custody are from the Paris region and range in age from 31 to 40, said the prosecutor, Laure Beccuau, whose office is heading the investigation.

—Associated Press November 25, 2025

Louvre spent too much on art and not enough on security, audit finds

The report was completed before the heist but noted persistent delays in renovations of the museum.

“The theft of the crown jewels is, without a doubt, a deafening wake-up call: this pace is woefully inadequate, these delays are far too long.”

—The Financial Times November 6. 2025

Louvre heist suspect is social media star and former museum guard, reports say

The suspect had worked as a security guard at the Pompidou Centre art museum. Abdoulaye N’s criminal record includes 15 offenses: possession and transport of drugs; and causing danger to others. He was also convicted of robbing a jewellery store in 2014.

—The Guardian November 5. 2025

French police arrest 2 Louvre jewel heist suspects amid manhunt

Both suspects are French nationals who live in a suburb of Paris. One of the suspects has dual citizenship in France and Mali, and the other is a dual citizen of France and Algeria. Both were already known to police from past burglary cases.

—GMA October 26, 2025

Arrests made over jewel heist at the Louvre, French prosecutors sayA huge police operation has been underway to locate the four thieves who were captured on camera making off with eight pieces from the museum in a daylight robbery early last Sunday.

—NBC October 26, 2025

‘It’s Got to Be an Inside Job’: Jewelry Thieves Weigh In on Louvre Heist

"The heist was far from a flawless operation. The thieves ditched gloves, a helmet, vest and other items that the authorities have said contained traces of DNA."

'They’re not experts,' he said. 'They’re opportunists.'

New York Times October 25, 2025

Louvre’s Director Says Key Camera Was Pointing Away From Jewelry Thieves

The museum’s director acknowledged on Wednesday that much of its security system was badly outdated and that the only exterior camera near the thieves’ entry point was facing away from them.

The security system kicked in only once the thieves had breached a window with power tools, shaving off crucial several minutes from the authorities’ response time.

New York Times October 22, 2025

Police probe new video showing Louvre jewel thieves escaping

"Investigators hunting the gang behind the heist have also found traces of DNA samples in a helmet and gloves, prosecutors confirmed.

NBC October 22, 2025

FBI Provides Update in Gardner Art Heist Case

November 21, 2000 W. Thomas Cassano, Supervisory Special Agent for the Gardner Museum heist case said that "a tape inside the museum showed the thieves making four forays through the galleries.

After taking the two Rembrandt oil paintings

in their first trip, they removed Jan Vermeer’s oil painting “The Concert,” Rembrandt’s etching “Self Portrait,” and Govaert Flinck’s painting “Landscape with an Obelisk” during their second."

Antiques and the Arts November 21, 2000

| |

Read what the fuss is all about and the orginal

Read what the fuss is all about and the orginal